3. Types of Speciation

The Kingfisher Family

Speciation describes the way in which new, distinct species arise in the course of evolution. The kingfisher family provides good examples. Kingfisher species are widespread throughout the world although in Europe and much of Asia people know only one species, the Eurasian or commom kingfisher, a beautiful bird brightly, coloured in blues, greens and chestnut.

Eurasian Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis)

The River Kingfishers

The Eurasian kingfisher is associated with rivers, lakes and coastal regions and admired as a skilled catcher of fish. It has a massive range with populations from Ireland across Europe, North Africa, and Asia as far as the Solomon Islands in Australasia.

A Successful Bird

The kingfisher above was photographed on Samosir Island, Lake Toba, Sumatra. The last time I had seen a Eurasian Kingfisher was as a flash of colour as it raced down a small river at Tuckenhay, South Devon, UK, illustrating the remarkable range of this successful bird. Populations can be divided into a number of "sub-species", with differences in size and colour shade. A subspecies, unlike a species, is still capable of breeding with other subspecies so behavioural and genetic/physical (pheonotypical), differences have not yet reached the species level where interbreeding becomes impossible or at least highly unlikely.

Adaptation

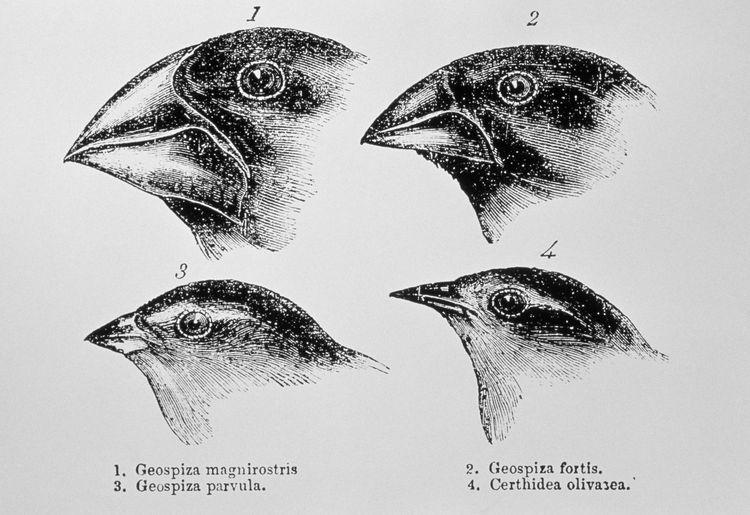

It is difficult to identify the environmental factors leading to these differences in the Eurasian kingfisher. We know from Darwin's study of finches in the Galapogos islands and recorded in his revolutionary work, "Origin of the Species" published in 1859, that a number of "adaptations" occurred with populations, many on different islands separated by stretches of ocean, in response to differing environmental conditions and the resulting natural selection.

Wikimedia Commons

Four of thirteen species of finch Darwin identified in the Galapagos Islands

Allopatric Speciation

The beaks of these seed, fruit and insect eaters have evolved through natural selection according to the available food source in their particular habitats. These beak adaptations are at least to some extent examples of "Allopatric Speciation" which results from physical barriers such as mountain ranges, deserts and oceans separating populations of a species. Such barriers can arise abruptly, as in the case of volcanic activity, or more gradually as with changes in sea level, or the birds may simply fly or are are wind blown to new territory to establish new populations.

To return to our Eurasian kingfishers, they may have such a vast range that they are simply responding to differing enviromental conditions such as climate, vegetation and diet. Or it may be merely "Genetic Drift" where gene combinations begin to dominate a population by chance with neither an advantage or disadvantage where survival is concerned.

114 Kingfishers

This is far from the end of the kingfisher story. It may come as a surprise to Europeans to learn that there are in fact 114 species of kingfisher divided into three families and 19 genera. They all have in common large heads with long, pointed beaks, stubby tails and short legs. Most have vividly coloured plumage with very little difference between males and females. The majority of species are tropical and many inhabit forests and not necessarily near water.

Malachite Kingfisher (Alcedo cristatav)

A common resident in watery habitats in sub-Saharan Africa, the malachite kingfisher's plumage suggests a close relationship to the Eurasian Kingfisher although a smaller more vividly coloured version. It is another example of the river kingfishers (Alcedininae). This bird was photographed at Rondevlei, Western Cape, South Africa. Note the long, slim beak of a diving kingfisher.

Bio-diversity and the Tropics

Why are there so many more species closer to the equator than in temperate regions? This follows a general pattern where there is far greater bio-diversity in the tropics and subtropics compared with temperate and arctic regions simply because of a more accommodating climate and a much richer food supply.

Cerulean Kingfisher (Alcedo coerulescens)

Origins of the Kingfisher

How did eurasion kingfishers move south and multiply? They didn't! DNA analysis and fossil records show that populations of kingfisher started in Australasia and SE Asia and moved into Europe and Africa at a much later date. The cerulean kingfisher also a river kingfisher and another example of the rich variety of kingfishers in tropical regions. It is unique to Indonesia inhabiting flooded paddy fields, canals, streams and tidal estuaries and feeding mainly on a diet of fish for which it dives from a conveniently located perch overlooking water. This beautiful bird above was photographed in West Bali National Park.

The Ecological Niche

And why are there so many different species of kingfisher? Probably a variety of factors. For instance, in Papua New Guinea where there are 26 species, it may be related to the challenging topography and the ridges and valleys that define much fo the land resulting in allopatric speciation. And allopatric speciation probably applies to the many species that populate the thousands of islands in the region. There is also evidence to support "Sympatric Speciation": a population may diverge because they occupy different "ecological niches". Large populations which compete for limited resources may divide with smaller populations choosing or driven to different habitats or to seek different strategies for obtaining food.

White-throated Kingfisher (Halycon smyrnensis)

The Tree Kingfishers

For instance, the forest species of kingfisher (tree kingfishers, Famliy Halcyoninae) have evolved away from water and eat insects, small reptiles and even small mammals and eggs. They are physically different from their water based cousins. The river kingfishers (Family Alcedininae) have evolved beaks that are long, and sleek to enable them to hunt fish more effectively, reducing drag and the amount of disturbance when they dive into the water and giving them greater speed underwater. Tree kingfishers, on the other hand, have thicker, more powerful beaks that are better adapted for their land based hunting. Note the strong, powerful beak of the the large white-throated kingfisher above that has evolved to enable the hunting of amphibians, reptiles and small mammals. The white-throated kingfisher is a widely distributed resident across Asia from the Sinai Desert, through the Indian subcontinent and south East to the Philippine Islands. The photograph above was taken in the Botanic Gardens, Bali, Indonesia.

Pied Kingfisher (Ceryle rudis)

The Water Kingfishers

The tree kingfishers and the river kingfishers are joined by a third family, the water kingfishers (Family Cerylinae). The several species of water kingfishers which monopolise the kingfisher family in the Americas probably originated in Asia. The pied kingfisher (above in Kruger National Park, South Africa) is the most common water kingfisher in sub-Saharan Africa and also in southern Asia from Turkey to India and as far as China. Not only does this most successful species, have a distinctive non irridescent black and white plumage and crest, but they also hunt by hovering 15 to 20 meters above the water for several minutes before diving at lightening speed, beak first, to take fish, often eating small prey in flight without returning to a perch. Other kingfishers can hover but only for seconds and need to return to a nearby perch. The sustained hovering strategy enables pied kingfishers to hunt over large lakes or in wide estuaries which are inacessible to other species of kingfishers. This is an excellent example of sympatric speciation as a response to competition for a limited food supply.

Pied Kingfisher

The pied kingfisher hovering in the picture above was a frequent visitor at low tide to Leisure Island, Knysna, South Africa.

Another bird that uses hovering as its primary hunting mode is the kestrel, but the two species are unrelated, another case of "Convergent Evolution". Convergent evolution occurs when two species from entirely different ancestry evolve similar features in order to retain maximum effectiveness in their natural habitat.

Reproductive Isolation

Whether speciation occurs through sypatric or allopatric speciation, or through other causes, gene mutations accumulate in the different populations over a period of time which may be tens of thousands or millions of years. Environmental differences may lead to a particular dominant genetic variable or "allele". These genetic changes lead to different characteristics between the two populations. Differences become so pronounced that populations can no longer breed with each other. The changing characteristics may even be behavioral: a change in mating displays or song can be sufficient to at first discourage and then prevent mating as the differences grow. More of that in the next section.