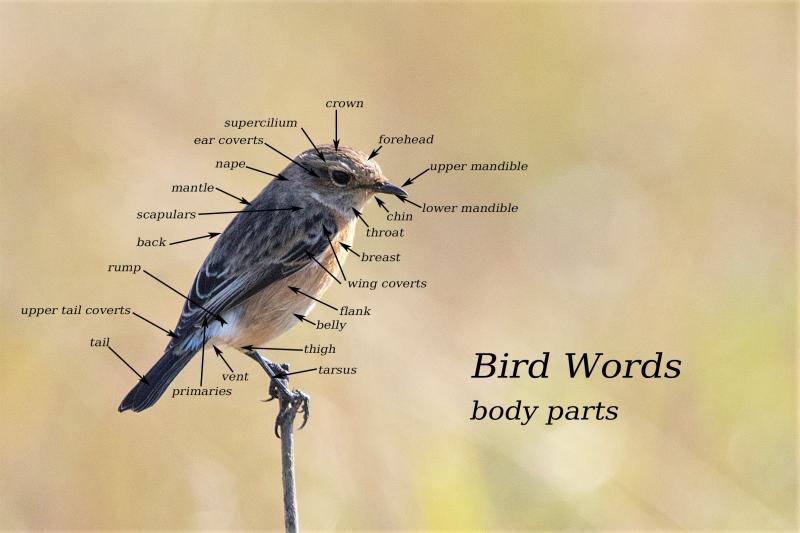

Bird watchers use a variety of clues in order to identify birds. For most of us, physical appearance is the starting point. Body shape and size, beaks, legs, eyes and plumage all feature in a bird's profile. Let's start with the basic vocabulary needed to describe the appearance of a bird. For instance a description may refer to the pronounced white "supercilium" of the species, or the bright red "vent", or the black and white striped "primaries". Below is an introduction to some helpful terms.

African Stonechat (female) St Lucia Wetlands, South Africa

Familiarity with body parts can help with identification. The name of a bird often refers to a conspicuous feature. Often, but not always, it is a reference to a colour in all or part of the plumage. The first bird below is named after its black nape. The two that follow are "pied" which means black and white.

Although plumage is one of the most obvious and distinctive means of identification, it can also be one of the most confusing.

1. Plumage Colour

Males and Females with Similar Plumage (Monomorphic)

Some species are immediately identifiable from their plumage and the task is made easier when adult male and female birds are similar or even identical. Look closely at the male and female black-naped terns below.

Black-naped Tern

Terns are lightly built, slender birds with narrow wings, forked tails, long beaks and relatively short legs. Most species have pale grey upper parts and are white when viewed from below. These adaptations equip them for long distance flight and for snatching prey such as small fish and shrimps from the surface of the sea.

Male and female terns usually have similar plumage. The black-naped terns in the photograph above are no exception. They were photographed at khao Kolok, Thailand.

Males and Females with Slight Differences

Next we have a pair of pied kingfishers. Can you see any differences between the male and the female?

Pied Kingfisher

This pair of pied kingfishers photographed at Rondevlei, Western Cape, South Africa, are at first glance similar. A closer look shows a difference in the black bands across the chest and breast. The male has the double band across the breast while the female has a single, broken band. The pied kingfisher has the typical stocky build, large head and long pointed beak of the kingfisher family.

Males and Females with Contrasting Plumage (Sexual Dimorphism)

Now have a look at these two Eurasian Siskins.

Eurasian Siskin

Eurasian siskins are a small bird with the typical strong rounded beak of the finch family, ideally suited for breaking open seeds and nuts. Note the male Eurasian siskin in breeding plumage on the right. He has evolved brightly coloured plumage to attract the female siskin and to intimidate rivals. On the other hand, the subdued greys and browns of the female siskin provide camouflage when she sits on the nest and feeds her young. Differences between male and female birds is known as sexual dimorphism and may range from small differences such as weight and size to completely different plumage.

Why Do Some Female Birds Lack Camouflage?

Why hasn't the female black-naped tern evolved camouflage plumage? Maybe it is because black-naped terns nest on reefs, cays and islands where there are few predators. Female kingfishers have a different reason for the lack of camouflage. Kingfishers excavate tunnels in vertical banks or find existing holes and crevices for their nests so spend much of the breeding season in the dark and unseen.

One final, and very challenging example of dimorphism:

Little Pied Flycatcher

If I had not seen the male and female together in the botanical gardens, Bali, I doubt if I would have realised they were the same species. The contrast between the striking black and white pattern of the male little pied flycatcher and the dull browns of the female, provides an excellent example of sexual dimorphism. The female is also a great example of what birdwatchers call "SBJs" - "Small Brown Jobs". These are small brown birds that are very difficult to identify and which are very often either females or juveniles. There is often some resemblance between mother and juvenile of the same species when for both, the first priority is camouflage. The tiny size of the little pied flycatcher aids identification.

Juveniles

How often when confronted with an apparently new species do we struggle to find a match in the bird book or online site? Often the problem is because we are not dealing with mature adults. Juvenile plumage can be very different from the adult equivalent, particularly when both parents share similar plumage. Natural selection (see speciation section) ensures that camouflage is the priority for immature and inexperienced birds rather than ostentatious display. Here are a couple of examples.

Scaly-breasted Munia - Adult (left) Juvenile (right)

I was puzzled when I spotted a seed eater in a tree next to the verandah of the resort where I was having breakfast on the island of Phuket. A new species for me? And one that proved very difficult to identify. The size and shape as well as the beak were similar to the munias I had observed in SE Asia. But the plain cream and brown plumage was new. It took some time for me to make the link between this bird and the fairly agitated pair of adult scaly-breasted munia I had seen in the same tree the previous day. A little extra research and I realised that this was a juvenile of that species.

Illustrated below is another example of a bird that I found challenging to identify.

Black-crowned Night Heron Juvenile (left) Adult {right)

I photographed the juvenile black-crowned heron on the left on Thesen Island, Western Cape, South Africa. I observed it several times leading a sedentary life perched in a tree in the middle of a small lake. I knew from physical features like the body shape,long sharp beak and featherless legs that it was a member of the heron family. But I only identified the species after research showed that only the black-crowned night heron has the red eye pigmentation. It is a diagnostic feature or distinguishing characteristic. The stippled brown of the juvenile provides excellent camouflage against the background of small trees and bushes. Note the more striking adult on the right photographed in Suan Rot Fai, Bangkok, Thailand (The species has a very wide range).

Both juvenile and adult seemed inactive. This is because they hunt at night and in the early morning and rest during the day. They have found an "ecological niche" (see speciation section) where there is no competition from other, "diurnal" (active in daytime) herons and bitterns.

Note that eye colour can help identify species. But it can also be misleading as eye colour changes as some species mature, as we see in my next example below.

Some birds take more than a few months to grow adult plumage. A good example is the satin bowerbird. Both the male, female and juvenile satin bowerbird have similar plumage until about their fifth year when young males begin to develop reaching fully mature plumage in their seventh year.

Satin Bowerbird Juvenile and Female (left). Maturing Male (right)

The bird on the right could be either a male or female immature satin bowerbird, or a mature female satin bowerbird The bird .on the right is a male satin bowerbird approaching full maturity when it will have an impressive glossy blue-black plumage. The male above already has the striking violet-blue iris and yellow beak of the fully mature male. Photographed in Toowoomba, Queensland.

In many species, non-breeding plumage i provides camouflage and is duller with less obvious markings and closer to the female in appearance. During the breeding season the mating urge takes precedence over safety and a display of bright colours attracts a female and deters rivals. Some species retain the same plumage throughout the year as illustrated by the mature male satin bowerbird above. Others wear breeding plumage for the whole of spring and summer while for others it is a matter of a few weeks.

Adult Male (breeding plumage) Adult male (eclipse plumage) Adult Female Juvenile

The mallard ducks above illustrate the differences between males in breeding plumage and non-breeding (eclipse) plumage as well as the similarity beween male eclipse plumage, female plumage and juvenile plumage. How do you tell the diiference? Note the yellow bill of the adult male, the orange and black bill of the female, and the grey-green bill of the juvenile.

Finally, in this section, we look at bird in eclipse plumage that belongs to one of three different species..

Pond Heron

The pond heron is a common throughout Asia. The non-breeding plumage patterned in various shades of brown is surprisingly difficult to see from a distance on the banks of a lake or river. It is also virtually identical in the Indian pond heron, the Javanese pond heron and the Chinese pond heron, although the breeding plumage of the three birds is strikingly different. Photographed in Suan Rot Fai Park, Bangkok.

Chinese Pond Javan Pond Heron

The Chinese and Javan pond heron in breeding plumage are handsome birds and very different from their non-breeding counterpart and are distinct from each other.. Photographed in Ayutthaya, Thailand..

2. Size and Shape

Imagine each bird as a silhouette. Distinguishing features might be size, body and beak shape, leg length and perhaps wing shape if the bird is in flight. Maybe a plumage feature is visible, for instance, a crest or an exotic tail.

Racket-tailed Drongo

There is no mistaking the raquet-tailed drongo from its silouette. A photograph taken from below and into the light on Koh Samui, Thailand. Because we frequently look towards the light to view or photograph a bird, the ability to identify a bird from such features is very useful. It is also often a starting point for establishing the family to which a bird belongs even when there are other visual (or auditory) clues available.

When I first saw the bird below in Toowoomba, Australia my comment was: I've never seen a pigeon with a crest before".

Crested Pigeon

I even called it a "crested pigeon" which turned out to be its name. This demonstrates how a physical feature, whether it is a prominent colour or distinctive shape, can aid identification and even the name of the species.

Size is an obvious first clue to the identity of a species. For beginners, it is useful to have yardsticks: smaller, bigger or similar in size to a sparrow, a feral pigeon or a domesticated goose? These are fairly ubiquitous (found everywhere) species. You may prefer other yardstick species depending on your geographical location.

Body Shape is almost as variable as size. Look at the two colourful birds below,

Blue-tailed Bee-eater Eurasian Kingfisher

The strealmlined long tailed bee-eater presents a very different profile compared to the stocky, large headed and short tailed kingfisher. The beaks are also different. The more delicate, curved beak of the bee-eaterr contrasts with the strong, straight beak of the kingfisher. Chapter one provides a more detailed look at species with different types of beak. Over time, practice will enable you to use shape and size to identify the family to which a bird belongs.

4 Beaks and legs and colour differences

Beak colour can also aid identification. There are two species of tern in the small flock below

Sandwich tern and Greater Creasted tern

Note the yellow beak of the great-crested tern in the foreground and the black beak with a yellow tip of the sandwich tern in flight in the upper left hand corner. Incidentally, note the much larger white-breasted cormorant top right and the black oysterctatcher with the distinctive bright red bill just visible in the background, Photographed at the Goukamma River Estuary, Western Cape, South Africa.

Leg length and colour are useful diagnostic features. Many long legged birds are classified as waders, They are usually found in or close to water where the advantage of long legs is most apparent.

Greenshank Common Redshank

The greenshank and common redshank are waders and are similar in appearance. Tthe greenshank's larger size is only obvious when the two species are seen together. The easiest way of distinguishing the two quite similar species is by leg colour. The clue is in their names as shank refers to the upper part of the leg. The two photographs above, taken in Sam Roi Yot, Thailand also show the less obvious difference in the colour of their beaks,

Birds in Flight

Many species present differently when in flight and have distinctive plumage, wing and body shape and flight styles.

White-breasted Cormorant

This large, imposing bird was flying to a nesting colony in trees on the coast of Incaha Island, Mozambique. A distinctive heavy build and light coloured body contrasting with dark wings and tail, coupled with the cormorant beak, makes identification relatively straight forward.

White-backed Vulture

With the distinctive broad, slotted wings of a soaring raptor (see Feathers/Aerodynamics section), this white-backed vulture has a bulky, pale body and easily recognisable two tone wings. Note also the raptor's beak. Photographed in Hluhluwe National Park, Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa.

Red Kite

Another raptor with a strking wing pattern and white, black tipped tail feathers. Photographed at Bwlch Nant Yr Arian Nature Reserve, Wales.

Crested Serpent Eagle

Many of the raptor family have complex wing patterns that can be difficult to distinguish when the bird is soaring high above you. You can research raptors that inhabit a particular region and then compare wing patterns. I photographed this crested serpent eagle in North West Bali, Indonesia.

Water Dikkop or Water Thick-knee

The rapid, direct, low level flight of many waders means they are harder to photograph and you are as likely to see the upper surface of the wing as the lower. This water dikkop, a member of the stone curlew family, on a beach at Plettenberg Bay, Western Cape, South Africa, has a wing pattern with distinctive white spots that separates it from other species.

In conclusion to identify a bird in flight look out for the following:

Shape and width of wings (see also Flight section/Aerodynamics).

Body and wing markings - every species is different.

Body shape and how big is the body compared to the wings.

Tail - length, shape, colour and markings.

Position of legs and head while in flight.

Flight rhythm - regular or irregular? rapid or slow? Soaring and gliding? (See Feathers chapter, Flight section for more details).

Purpose- Circling? Diving? Hovering? Flying purposefully in a straight line? Flitting from place to place?

Call - Is the bird silent or calling as it flies? (see the sub section Bird Calls).

Numbers - In a flock? Alone? A pair?

Note that some of the above features overlap with the content of Section 3, "Behaviour".